ElizabethElizabeth left us thirty years ago today: April 6, 1981.

ElizabethElizabeth left us thirty years ago today: April 6, 1981.

Trite but true: I can hardly believe it has been that long.

I feel as though I talked with my Mamaw only yesterday, or maybe last week.

We shared a cup of strong, fragrant Louisiana coffee. She didn't say much besides the customary Hey Baby! spoken in her unique raspy, burnt-sugar southern drawl.

Her smile was bravely sweet if a tad bit forced.

I watched her eyes to see if the smile reached them, hoping the sight of me across the table brought her real joy.

Many demons of doubt and suspicion plagued my beautiful, complicated, conflicted grandmother.

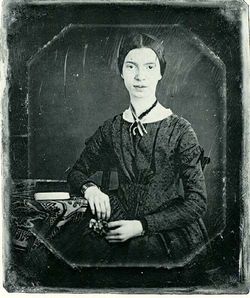

Born Mary Elizabeth Cassidy in Brookhaven, Mississippi, in the waning days of the Great War, she was an American girl who faced as much personal turmoil as was being felt by the world around her.

There would be a little sister, Genevieve -- or Genevee, depending on whom you ask -- in 1920. When the girls were still toddlers, their young mother's life came to a sudden tragic stop.

Leila McBride Cassidy, my great-grandmother and the girls' mother, had been the daughter of the Brookhaven, Mississippi, Chief of Police. Mr. McBride took his widower son-in-law to court and, together with their grandmother, won custody of his two baby granddaughters.

The girls had no more contact with their father from that point on. They were de facto orphans practically before graduating from diapers to step-ins.

One of her daughters: my mother

One of her daughters: my mother

Charles Cassidy returned to California from whence he had come, remarried, and fathered four additional children: two sons and a set of twin girls. He died sometime in the late '50s or early '60s, hit by a car as he walked across the street.

Whether it was done all at once or gradually is lost in the mist of years, but after the grandparents took quasi-legal possession of Elizabeth and Genevieve/Genevee (the girls were never actually adopted), they insisted that the girls go by McBride, their dead daughter's maiden name.

Until they were old enough to take back their legal name of Cassidy, and until each of them married, the girls were known as Elizabeth McBride and Genevieve/Genevee McBride.

My Mamaw never talked to me about her childhood, so I know nothing past what I just told you. She married Dorsey Rollins Sandifer on December 21, 1935, at the age of seventeen.

In June of 1937 her first baby was born: my mother, Patricia Ann. The little family lived on a dairy farm in Brookhaven for the first few years.

My mother tells a story of her mother, already expecting a second baby (my beloved Uncle Sherrill) who would be born in January of 1939, accomplishing an heroic maternal feat.

As the story goes, at Christmastime in 1938, if you were willing to wait outside the door of a particular place of business, while supplies lasted you'd be rewarded with a free gift: a little stuffed animal.

My grandmother, eight months pregnant, stood for a significant length of time in the cold with my eighteen-month-old mother on her hip, to get the toy for her firstborn daughter's Christmas.

Five of her great-great-granddaughters: (L to R) Emilia, Anna, Damaris (hidden), Lydia, Priscilla

Five of her great-great-granddaughters: (L to R) Emilia, Anna, Damaris (hidden), Lydia, Priscilla

Because that was all there would be in the way of presents. They were lucky to have food.

And they had one another, and they had love, and I like to think they were happy. Seems like it took less to be happy back then! You sure didn't need an iPhone or GPS to keep in touch or know where you were going.

I hope my grandmother realized that she gave my mother, and her other three children, one of the most important things she herself never had: a father who loved them and provided for them, and who didn't leave.

Because if a daddy can do little else, at least he can stay. And love his family, and provide food and shelter. That's what my Papaw did, even though at times, the Lord above knows, it wasn't exactly easy.

Shortly after the genesis of America's involvement in World War Two, my grandparents moved one state to the west and settled in Baton Rouge. They completed their family.

They lived on Chippewa Street, mere blocks from the banks of the snaky Mississippi River, practically in the shadow of the towering art deco State Capitol where Huey P. Long was assassinated in 1935.

Papaw would work at the Standard Oil plant on the river until he retired.

My grandmother died at the relatively young age of sixty-two. In those few years she was given on earth, it is anybody's guess whether she believed she had accomplished anything of value.

Her four children: (L to R) Dorsey Jr., Linda, Sherrill, Ann

Her four children: (L to R) Dorsey Jr., Linda, Sherrill, Ann

But I know she did and I'm not the only one who knows it.

For starters, she reared not one, not two, not three, but four bright, funny, intelligent, creative, talented, warm, loving, sincere, patriotic, God-fearing, hard-working children.

(Yes they're flawed, but then so are you and so am I. Like everyone else since Adam and Get Even messed up in the Garden of Eden, they were born with the sin nature. Between them they've made plenty of mistakes and, like their parents before them and their children after them, they have their share of shortcomings.)

Be that as it may and aside from the obvious fact that my own beloved mother is first in the lineup, I shudder to think what my life would have been without any one of these amazing people to love me, guide me, encourage me, teach me, nurture me, and pray for me.

Not to mention feed me. Mercy, can that crowd cook. Tears come to my eyes as I contemplate their individual and collective culinary wizardry. Whole lifetimes of unconditional love in a single fluffy biscuit, heap of crispy-golden fried okra, or steaming bowl of gumbo.

Incredible. Eat your hearts out because you'll never know.

In addition to being a stellar cook, my grandmother was an absolutely dazzling housekeeper. Try as I might, I cannot recall an iota of disarray in any one of the immaculate homes I remember her making.

Her domestic MO was never stuffy, though. Far from it. Although everything had a place and was perpetually in it, as a kid you didn't feel you were in peril of causing the earth to leave its axis if you touched this or that in the wrong way.

At least, I didn't.

Instead, Mamaw's house was a place of just enough warmth and just enough cool. The carpet was plush and clean under my elbows in front of her color television where I watched the NBC peacock unfurl its jewel-hued feathers to an instantly-recognizable xylophonic scale run.

Dorsey and Elizabeth Sandifer

Dorsey and Elizabeth Sandifer

Come bedtime, you didn't mind leaving your spot in front of the TV set because the sheets were soft but crisp and redolent of sunshine, and they held you like loving arms.

At Christmastime during the '60s she brought out a silver tinsel "tree," decorated it with a single color of identical ornamental orbs (usually red), and set an electric light at its base. A disc divided into four primary-color cellophane windows revolved atop the light, causing the phony branches to "change colors" as you watched in amazement.

(Informed as it was by Mamaw's lifelong affinity for the perilously-close-to-gaudy embellishment, to a child the tree was simply breathtaking. Not tacky in the least! Step off.)

Her furnishings, draperies, artwork, and accessories were tasteful and classy. There was a hush amongst her things that made you want to be an elegant person like her.

My lifelong fanatical love of beautiful music, while not necessarily formed at Mamaw's, was certainly encouraged there. She had a hi-fi that was bigger than some cars you see on the road these days. Mellow? Shut UP! The sound was like buttah, y'all.

I'd very carefully move her tall glass bottle ornaments off the shiny surface of the hinged mahogany lid she'd polished thousands of times. Never a speck of dust! You could see yourself.

The mysterious aroma of electronic circuitry and pressed black vinyl would meet my excited nostrils and I'd select a record.

If I close my eyes I can still hear the lush strains of Maria Elena. It was one of her favorites, and mine too. To this day the more lavish the orchestration, the more poignant the melody, the happier I am and the more connected I feel to my own past.

Mamaw set a proper table and the food was always beyond splendid. Whether you were having a bowl of cornflakes (something we often did because she loved them) or a no-holds-barred holiday repast, it was made special by her careful but unfussy attendance to detail.

She never said so but you just knew that while you were at Mamaw's, she wanted you to enjoy yourself.

Three of her great-granddaughters: my daughters (L to R) Erica, Audrey, Stephanie

Three of her great-granddaughters: my daughters (L to R) Erica, Audrey, Stephanie

And I did.

My grandmother had a great many personal problems and I won't enumerate them here because what would be the point. I loved her anyway.

Without actually telling me in words, she taught me so much. I learned from her that a woman should always look like a lady. No matter how much of a hurry she might be in, or how unwell she might have felt, my grandmother took pains with her appearance.

Mamaw was a bit of a clothes horse and no sartorial subtlety was beneath her notice. She always looked like what I associate with that old expression "bandbox fresh."

You would never catch my Mamaw at the grocery store without her hair and makeup done to perfection, and certainly not clad in sweatpants or blue jeans or anything remotely like them. She didn't own any sweatpants or blue jeans that I know of, and believe me the world was a better place for it.

Even at home, when no company was coming over, Mamaw would be decked out in one of her possibly hundreds of sets of glamorous silk pajamas. She had nearly as many pair of slippers, numbers of them gold, some of them turned up at the toe like a court jester.

She was a study in both natural and cosmetic femininity, and in the womanly art of putting forth your very best foot -- which in her case was always gorgeously shod -- no matter what the circumstance.

My grandmother would be dismayed at the paucity of care women take in clothing and grooming themselves to look like females -- much less ladies -- nowadays.

(After her funeral I stood in front of her open closet feeling sad, helpless, empty, and defeated. Instead of a pretty outfit from Goudchaux's, she'd been buried in a gauzy powder-blue pegnoir set purchased from the funeral home. She didn't need her cute clothes anymore. The brutal finality of that fact was difficult to comprehend.)

Many times in the early '70s she and I ran around the streets of Baton Rouge in her orange VW Bug. Like as not, Mamaw was chewing gum (but in a ladylike way) because she could never quite kick the smoking habit although I know she tried.

Two more of her great-great-granddaughters: my grandchildren Allissa (L) and Melanie

Two more of her great-great-granddaughters: my grandchildren Allissa (L) and Melanie

I can still see her meticulously-manicured hands resting lightly on the steering wheel, and the little pinky ring she wore that featured a tiny dangling dove.

(I took the ring to be a costume-jewelry symbol of my grandmother's faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, in Whose sacrificial death on the cross she had trusted as her only hope of heaven. I believe she is there today, and yes she walks on streets of gold so pure they are transparent. I believe the past thirty years have passed for her, in the presence of her Savior, like a mere moment. And I believe I'll see her again soon because like my grandmother, I've trusted in Him and Him alone.)

So as we tripped along the hot and humid Louisiana roads, on our way to the now-defunct Bon Marche Mall or maybe just to the TG&Y to shop for whatever caught our fancy, I watched Mamaw work her gum and guide the peanut-sized car practically without lifting an exquisitely-painted finger.

(As she lay in her coffin I stroked her hand one last time and lifted an index finger by one of her pretty fingernails. It was so cold! She wouldn't have liked the feel but she would've approved of the look.)

And so did I.

Mamaw's innocent antics are legendary in our family. She once returned a brand-new bathroom scale to the department store where she'd purchased it. Reason? It weighed her the same as the old one.

Treated to a professional baseball game at one point latish in her life, she was so bored, she fell asleep. At the seventh-inning-stretch, when everyone stood to sing Take Me Out to the Ballgame, she woke up and stood with them. Tucking her purse under her arm and turning to go, she said, "Thank God that's over."

One time when she was young, she and Papaw were sitting in the dark car at a drive-in movie. Mamaw's lips were chapped and she reached into her purse for a tin of lip balm. She smeared her mouth and resumed watching the film.

Sisters Genevieve (L) and Elizabeth Cassidy, circa 1922

Sisters Genevieve (L) and Elizabeth Cassidy, circa 1922

Only, as they drove home Papaw was moved to ask his wife why there was black stuff all over the lower part of her face.

She had actually rubbed mascara (or eye-blackin' as my Papaw called it) on her lips. Back then, mascara came in a little cake that you moistened and applied with a wee brush that lay in the tray beside it.

I call that an honest mistake.

My memories are vivid of Mamaw sitting at a picnic table at the home of one of her sons, a burgeoning mound of crawfish shells at her elbow, her fingers stained with crab boil. She could flat-out tuck in to a crawdad feast, my grandmother.

There are more tales but suffice it to say, she was a funny lady and didn't even know it. That's what made her so funny.

Mamaw was a complex person who struggled with a plethora of physical and mental difficulties, and I am sad to say these issues probably shortened her life.

A doctor whose name I do not know but whom I nevertheless regard as irresponsible prescribed medication that rendered her quasi-conscious for the last few years of her life. She ate little besides cornflakes and vanilla ice cream, subsisting on Fresca diet soft drink and Louisiana coffee so strong it threatened to dissolve the spoon you employed to stir it.

The last time I saw my grandmother was on my wedding day: June 16, 1979. She looked so pretty standing in the Georgia sunshine, but by then her affect was distinctly vacant.

When Stephanie was born in September of 1980, Mamaw sent my baby a tiny pink stuffed bunny rabbit. Like the little toy for which she'd patiently queued up so many years ago, to give to her own baby? I sensed a sameness of purpose.

I nestled the bunny in the corner of Steph's garage-sale Winnie-the-Pooh crib. When TG put Stephanie and me on a plane bound for Baton Rouge to attend Mamaw's funeral seven months later, the bunny was tucked into our luggage.

Two of her granddaughters: my big sister and me

Two of her granddaughters: my big sister and me

My Mamaw was not the effusive, doting kind of grandmother I tend to be. She never came close to smothering you because she was possessed of a certain intrinsic remoteness. There were debilitating insecurities. Things went on in her head that I firmly believe those closest to her never had a prayer of grasping, even to the limited extent that any of us are ever able to plumb the depths of our dearest loved ones.

Mary Elizabeth Cassidy Sandifer stands as that most wondrous of larger-than-life figures: an individual with individuality. As has been firmly established, nobody gets a do-over. If she could have another swipe at life, I imagine like most of us she'd tweak an event here, a deed there.

But if it were up to me, I doubt I could come up with a single thing I'd alter about my grandmother.

Except maybe to have her standing in front of me once more so I could say Mamaw, I love you. As long as I live, you will never be forgotten.

Oh, and ... see you soon.

Tuesday, April 12, 2011 at 09:44PM

Tuesday, April 12, 2011 at 09:44PM  A couple months back I was out in the sticks at my hairdresser's, when for some unknown reason the subject turned to tombstones.

A couple months back I was out in the sticks at my hairdresser's, when for some unknown reason the subject turned to tombstones.

Jennifer |

Jennifer |  9 Comments |

9 Comments |

![Hold Back the Dawn [DVD] Charles Boyer; Olivia de Havilland; Paulette Goddard](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/41AkExBJQsL._SL75_.jpg)